Anni Albers, née Annelise Elsa Frieda Fleischmann on June 12, 1899, was born into comfort and culture. Her father a furniture manufacturer, her mother descendant of the Ullstein publishing dynasty, she grew up surrounded by the objects and images of a prosperous Berlin. Art filled the rooms of her childhood, yet her own path toward it began hesitantly.

She first trained under the impressionist painter Martin Brandenburg, but the experience left her restless, unconvinced that painting was the language she was meant to speak — an uncertainty only deepened after a later encounter with Oskar Kokoschka. In 1919, aged 20, Albers turned to the Kunstgewerbeschule (School of Applied Arts) in Hamburg, hoping to find a more tactile, more grounded form of expression. Yet once more, she remained unenthused.

Anni Albers, née Annelise Elsa Frieda Fleischmann le 12 juin 1899, vit le jour dans le confort et la culture. Son père était fabricant de meubles, sa mère descendait de la dynastie éditoriale Ullstein, et la maison familiale débordait d’objets et d’images, témoins d’un Berlin prospère. L’art imprégnait chaque pièce, et pourtant, sa propre voie artistique se dessina lentement.

Elle se forma d’abord auprès du peintre impressionniste Martin Brandenburg, mais cette expérience la laissa insatisfaite, convaincue que la peinture n’était pas le langage qui lui convenait – un doute que renforça une rencontre ultérieure avec Oskar Kokoschka. En 1919, à vingt ans, elle s’inscrivit à la Kunstgewerbeschule (École des Arts Appliqués) de Hambourg, en quête d’un mode d’expression plus concret et tactile. Mais, une fois de plus, l’étincelle ne se produisit pas.

Great freedom can be a hindrance because of the bewildering choices it leaves to us, while limitations, when approached open-mindedly, can spur the imagination to make the best use of them and possibly overcome them.

In 1922, she applied to the Bauhaus in Weimar — a new kind of school that promised to dissolve the boundaries between art, craft, and life itself. Walter Gropius’s vision was radical: a workshop-based education where material, process, and structure took precedence over style. But for Anni, the reality was still defined by gendered limits. She enrolled in the preliminary course and then hoped to enter the glass workshop, where her future husband, Josef Albers, was studying. Instead she was steered into the weaving workshop.

Albers once again found herself unenthused, considering textiles too sissy, like needlepoint and the other things ladies do. At first. Because within the strict geometry of the loom, she discovered freedom: a logic, an order, a kind of architecture in thread. The vehicle of her lifelong creative pursuit.

Albers had found challenges she had so desperately craved. Early on, her weavings showed a rigorous abstract vocabulary: grids, geometric forms, and a subtle play of colour and texture. The Bauhaus context trained her to think about form, function, and material in integrated ways — lessons she not only absorbed but made entirely her own.

En 1922, elle postula au Bauhaus de Weimar – une école novatrice qui promettait de dissoudre les frontières entre art, artisanat et vie quotidienne. La vision de Walter Gropius était radicale : un enseignement centré sur l’atelier, où la matière, le processus et la structure prenaient le pas sur le style. Mais pour Anni, la réalité restait marquée par des limites liées au genre. Elle espérait ensuite intégrer l’atelier de verre, où étudiait son futur mari, Josef Albers. On la dirigea cependant vers l’atelier de tissage.

Au début, elle se montra peu enthousiaste, jugeant le textile trop féminin, comme la broderie et toutes ces choses que font les dames. Mais c’était sans compter sur la rigueur géométrique du métier à tisser : c’est là qu’elle découvrit la liberté – une logique, un ordre, une véritable architecture en fil. Le véhicule de sa quête créative pour la vie.

Albers avait enfin trouvé les défis qu’elle recherchait avec tant d’ardeur. Très tôt, ses tissages révélaient un vocabulaire abstrait rigoureux : des grilles, des formes géométriques et un subtil jeu de couleurs et de textures. Le contexte du Bauhaus l’avait formée à penser la forme, la fonction et la matière de manière intégrée — des leçons qu’elle n’a pas seulement assimilées, mais qu’elle a entièrement appropriées.

In 1925, Anni married Josef Albers, and, in 1930, received her Bauhaus diploma and took over as the head of the weaving workshop. But soon after, the political tides in Germany turned dark. As the Nazis rose to power, the Bauhaus faced ever-greater pressure and, in 1933, formally closed. Through the support of Walter Gropius and an invitation from architect Philip Johnson, Anni and Josef Albers made the leap across the Atlantic to the newly founded Black Mountain College in North Carolina, where Josef would go on to establish a curriculum in visual design. The couple arrived at New York Harbour on Thanksgiving Day in 1933.

The move across the Atlantic was more than geographic; it was an entry into a radically different creative ecosystem. Black Mountain, experimental, small, and fiercely independent, offered a workshop culture that echoed the Bauhaus in spirit but with a looser, more intimate ethos. Here, teaching and making were inseparable. And so, for Anni, the classroom became a laboratory, a place where she explored weaving as a form of thought, a practice rooted in structure and material intelligence rather than mere craft.

En 1925, Anni épousa Josef Albers, et, en 1930, elle obtint son diplôme du Bauhaus et prit la direction de l’atelier de tissage. Mais peu après, les vents politiques en Allemagne tournèrent au sombre. Avec l’ascension des nazis, le Bauhaus subit des pressions croissantes et, en 1933, ferma officiellement ses portes. Grâce au soutien de Walter Gropius et à une invitation de l’architecte Philip Johnson, Anni et Josef Albers traversèrent l’Atlantique pour rejoindre le tout nouveau Black Mountain College en Caroline du Nord, où Josef allait mettre en place un programme de design visuel. Le couple arriva au port de New York le jour de Thanksgiving 1933.

Ce déménagement ne se limitait pas à un changement géographique : il signifiait l’entrée dans un écosystème créatif radicalement différent. Black Mountain, expérimental, petit et farouchement indépendant, offrait une culture d’atelier qui faisait écho à l’esprit du Bauhaus, mais avec une approche plus souple et intime. Là, enseigner et créer étaient indissociables. Pour Anni, la salle de classe devint alors un véritable laboratoire, un espace où elle expérimentait le tissage comme une forme de pensée, une pratique ancrée dans la structure et l’intelligence matérielle, bien au-delà du simple artisanat.

Usefulness does not prevent a thing, anything, from being art. We must conclude, then, that it is the thoughtfulness and care and sensitivity in regard to form that makes a house turn into art, and that it is this degree of thoughtfulness, care, and sensitivity that we should try to attain.

Beyond the studio, Albers’s curiosity carried her across continents. She travelled through Mexico and deep into South America, studying pre-Columbian textiles and artefacts with the eye of both an artist and a scholar. She sketched, photographed, and analysed each weave she came across — not to imitate but to learn from their structural logic. These were journeys that not only expanded her visual vocabulary. They deepened her appreciation for the ways craft could carry knowledge across time and culture.

In 1949, the Alberses left Black Mountain — largely because the college was small, financially precarious, and experimental to the point of instability. Josef was offered a position at Yale University, where he would help shape a burgeoning programme in design. For Anni, the move meant access to better facilities, more resources, and a wider circle of students and collaborators.

It also marked a turning point in her public recognition: later that year, she held her first solo exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art in New York — an exhibition that not only affirmed her individual achievement but also sparked a broader revaluation of textiles in the modern art discourse.

Au-delà de l’atelier, la curiosité d’Albers la porta à travers les continents. Elle voyagea au Mexique et profondément en Amérique du Sud, étudiant les textiles et artefacts précolombiens avec le regard à la fois d’une artiste et d’une chercheuse. Elle esquissa, photographia et analysa chaque tissage rencontré – non pas pour imiter, mais pour en comprendre la logique structurelle. Ces voyages ne firent pas seulement évoluer son vocabulaire visuel : ils approfondirent sa compréhension de la manière dont l’artisanat peut transmettre le savoir à travers le temps et les cultures.

En 1949, les Albers quittèrent Black Mountain, un collège petit, fragile financièrement et tellement expérimental qu’il en devenait instable. Josef accepta un poste à l’université de Yale, où il contribuerait à bâtir un programme de design en pleine expansion. Pour Anni, ce déménagement ouvrait l’accès à de meilleurs ateliers, davantage de ressources et un réseau élargi d’étudiants et de collaborateurs.

Cette année-là marqua également un tournant dans sa reconnaissance publique : elle présenta sa première exposition personnelle au Museum of Modern Art de New York — un événement qui confirma son talent et participa à redéfinir le rôle du textile dans l’art moderne.

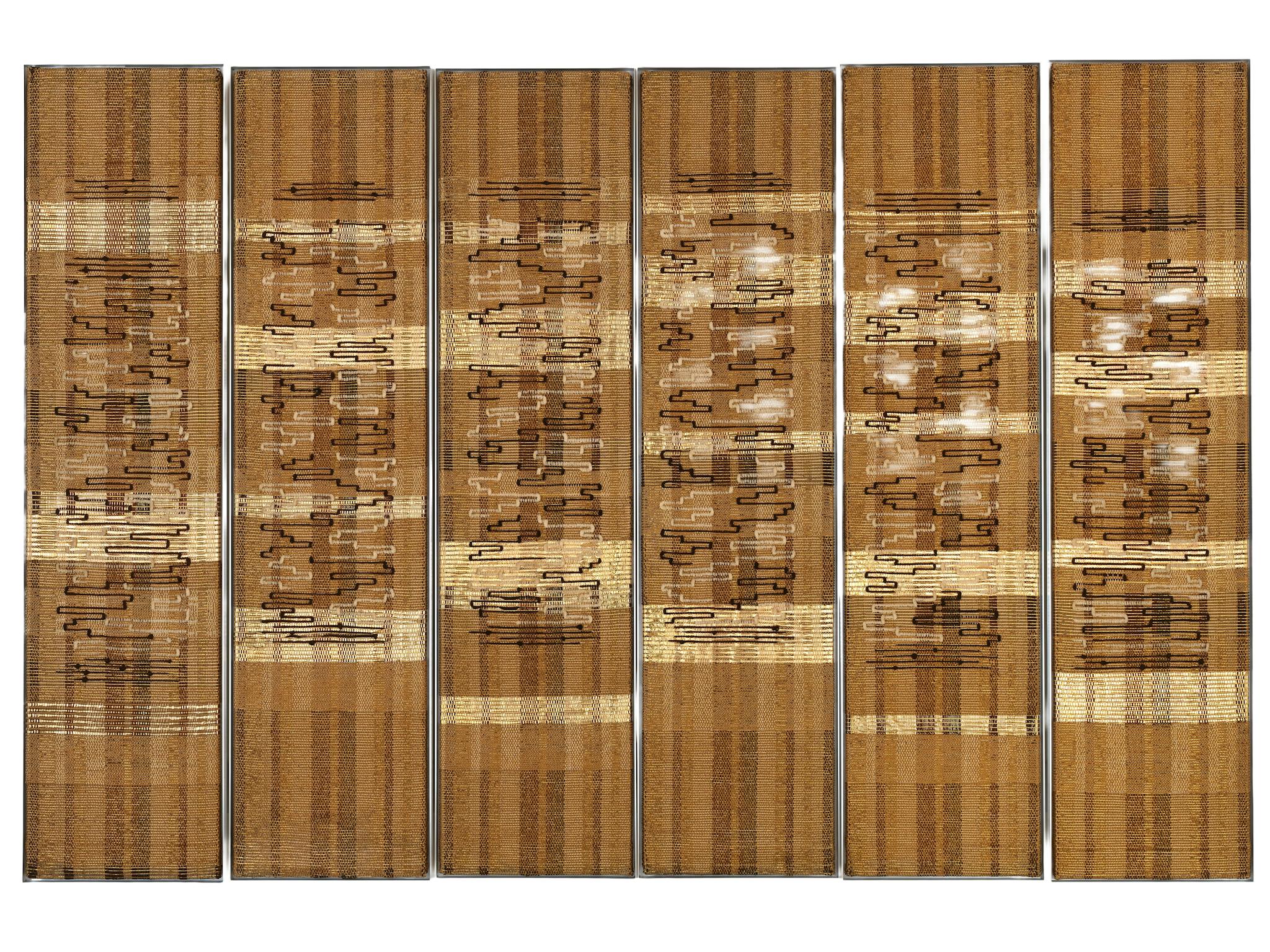

Meanwhile, Albers entered a more industrial and design-orientated phase of her career. She extended her practice into industrial design, creating textiles for mass-produced furniture for manufacturers such as Knoll and collaborating with architectural projects like the Harvard Graduate Center and the Rockefeller Guest House. And by the 1960s, she began translating her disciplined attention to the principles into printmaking: etching, lithography, and screen-printing allowed her to explore line, form, and rhythm on paper with the precision that had shaped her work at the loom.

In 1965, Albers published On Weaving, her most influential written work — a book that sits somewhere between an artist’s manifesto, a technical manual, and a meditation on perception. It distilled decades of her thinking about textiles, structure, and the act of making. Yet only five years later, in 1970, she gave up weaving altogether, turning fully to printmaking as her primary medium of artistic expression. Maybe not least because printmaking, as Albers herself once said, allows for broader exhibition and ownership of work. As a result, recognition comes more easily.

Dans le même temps, Albers entama une phase plus industrielle et orientée design dans sa carrière. Elle étendit sa pratique au design industriel, créant des textiles pour le mobilier produit en série pour des fabricants comme Knoll et collaborant à des projets architecturaux tels que le Harvard Graduate Center ou la Rockefeller Guest House. Dans les années 1960, elle commença à transposer cette rigueur et cette attention aux principes dans la gravure : eau-forte, lithographie et sérigraphie lui permirent d’explorer la ligne, la forme et le rythme sur papier avec la même précision qui guidait son travail au métier à tisser.

En 1965, Albers publia On Weaving, son ouvrage le plus influent — à mi-chemin entre manifeste artistique, manuel technique et méditation sur la perception. Le livre condensait plusieurs décennies de réflexion sur le textile, la structure et l’acte de créer. Pourtant, seulement cinq ans plus tard, en 1970, elle abandonna définitivement le tissage pour se consacrer pleinement à la gravure comme principal médium d’expression artistique. Peut-être pas le moindrement par hasard, comme elle le souligna elle-même : la gravure permet une plus large diffusion et propriété des œuvres, et, par conséquent, une reconnaissance plus facile.

Being creative is not so much the desire to do something as the listening to that which wants to be done: the dictation of the materials.

By the time she died on May 9, 1994, in Orange, Connecticut, Anni Albers had woven, quite literally, a radically changed art world. But only in more recent years have institutions — the Peggy Guggenheim Collection in Venice (1999), Tate Modern (2018), and currently Zentrum Paul Klee in Berne — fully begun to acknowledge her achievements and finally awarded her the recognition long overdue.

Anni Albers’ life story is one of flexibility, resilience and quiet ferocity. She accepted the seeming otherness of her medium and transformed it into an aesthetic of substance; she accepted limitation and turned it into a form. Her work invites us to listen to surfaces, to value the hidden architecture. And to remember that, sometimes, what seems humble — a thread, a line, a pattern — can carry the weight of grand ideas.

Lorsqu’elle s’éteignit le 9 mai 1994 à Orange, dans le Connecticut, Anni Albers avait, au sens propre, tissé un monde de l’art profondément transformé. Mais ce n’est que ces dernières années que les institutions – la Peggy Guggenheim Collection de Venise (1999), la Tate Modern (2018) et actuellement le Zentrum Paul Klee à Berne – ont pleinement commencé à reconnaître ses accomplissements, lui accordant enfin la reconnaissance qui lui était due depuis si longtemps.

La vie d’Anni Albers est celle de la souplesse, de la résilience et d’une tranquille férocité. Elle accepta l’altérité apparente de son médium et la transforma en une esthétique de substance ; elle accepta les contraintes et les transforma en forme. Son œuvre nous invite à écouter les surfaces, à apprécier l’architecture cachée. Et à nous rappeler que, parfois, ce qui semble humble – un fil, une ligne, un motif – peut porter le poids des grandes idées.

From November 7th, 2025, to February 22nd, 2026, the Zentrum Paul Klee will host Anni Albers. Constructing Textiles, the artist's first solo exhibition in Switzerland. The show will feature works spanning all periods of her career, with a special focus on her architectural interventions, highlighting the interplay between art, textiles, and architecture — the threads between building and weaving in Albers’ practice.

zpk.org

Du 7 novembre 2025 au 22 février 2026, le Zentrum Paul Klee accueillera Anni Albers. Constructing Textiles, la première exposition personnelle d’Anni Albers en Suisse. Le parcours présentera des œuvres couvrant toutes les périodes de sa carrière, avec un accent particulier sur ses interventions architecturales, mettant en lumière les interactions entre art, textile et architecture — les fils qui relient construction et tissage dans la pratique d’Albers.

zpk.org